Serbian Opal Mining Community

Coober Pedy: Diverse opal mining town

Exterior of the Church of St. Elijah

Exterior of the Church of St. ElijahCoober Pedy is one of the most famous, and unique, historical landmarks in Australia. Ever since opal was discovered in the northern South Australia town in 1915, Coober Pedy has been a home to several major Australian industries including opal mining, film making, and engineering. The promise of fortune has consistently lured people from all walks of life to Coober Pedy to take their chance at striking it rich. As a result, Coober Pedy is one of the most diverse places in Australia, where immigrants, Indigenous peoples and other minority groups found a safe haven in a sometimes unfamiliar land.

History of Serbian Migration to Australia

After World War II, there was a mass exodus of immigrants desperate to leave battle scarred Europe. One of the countries that had suffered the greatest losses was Serbia. After the Serbian monarchy refused to ally themselves with Hitler’s Axis powers, the state was invaded and destroyed by Nazi and fascist military forces. Thousands died and hundreds of secular and sacred sites were razed by bombs. The years after the war were not much better. Serbia fell under a tumultuous communist rule. After years of political and social turmoil, many Serbs made the decision to emigrate, with large populations settling in North America and Australia.

Opal Mining

These events coincided with the post-war opal mining boom that was occurring in Australia. Although first settling in major cities like Melbourne and Adelaide, racism and discrimination, as well as the draw of opal mining, led many immigrants to make their way to the nearest field. Away in the Outback, it was much easier for Balkans to connect with one another and feel a sense of community and normalcy. It also created an opportunity for the newly appointed miners to come together and keep the traditions of their home countries alive.

Serbian Orthodoxy

In 1993, the second generation of Serbian opal miners made the decision to build an Eastern Orthodox church, so that they could finally have a proper house of worship in Australia. Serbian Orthodoxy has been the primary religion of the Balkan states since the thirteenth century. It is an autocephalous, meaning ecclesiastically independent and self governing, religion. Such as the Catholics are led by the pope, Serbian Orthodox Christians are led by a “Patriarch”. Under the Patriarch, each region of the world is governed by a bishop that oversees the operations of the monastery and churches in that particular area.

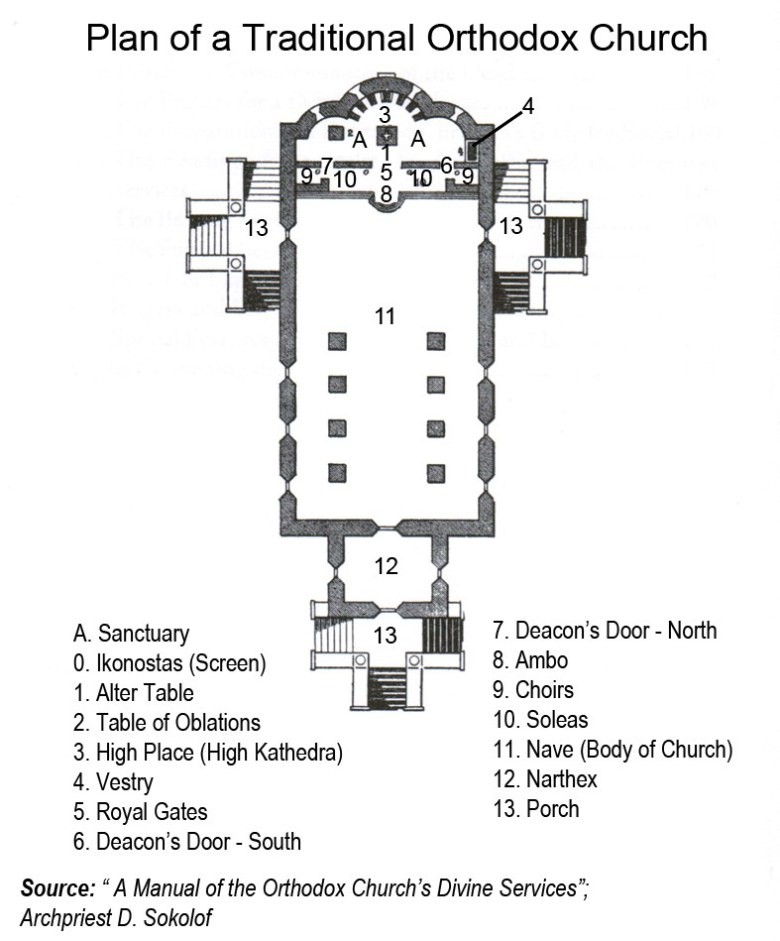

Eastern Orthodox Church Architecture

Eastern Orthodox churches are typically incredibly ornate and intricately decorated structures built in the Byzantine style of architecture. Famous examples include the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow.

Each Eastern Orthodox church is a symbolic rendering of the Kingdom of God. There are three different shapes that Orthodox churches are usually built in:

Cross: Representing the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Rectangle: Representing Noah’s ark.

Star: Representing the North Star and the guidance of the Holy Spirit down the path of righteousness.

Regardless of building shape, the layout of the interior follows a standard church design. In the very back is the narthex, which symbolizes the earthly plane. Here is where congregants can leave candles and offerings at the shrine of the church’s patron saint. In the center of the church is the nave. The word “nave” is derived from the Greek word naus, meaning “ship”. This is another reference to Noah’s Ark. On one side, female parishioners stand in prayer, and on the other, men, just as there was one of each gender of each animal saved during the biblical flood. At the front of the interior is the iconostasis. The iconostasis consists of one central door flanked on either side by two smaller ones, all completely adorned with images of the patron saint, the Holy Spirit, the Virgin Mary, and other sacred figures. Behind the doors is the altar room. The altar room always faces the east, the direction of sunrise. No one is allowed in this room without the express permission of the church’s bishop.

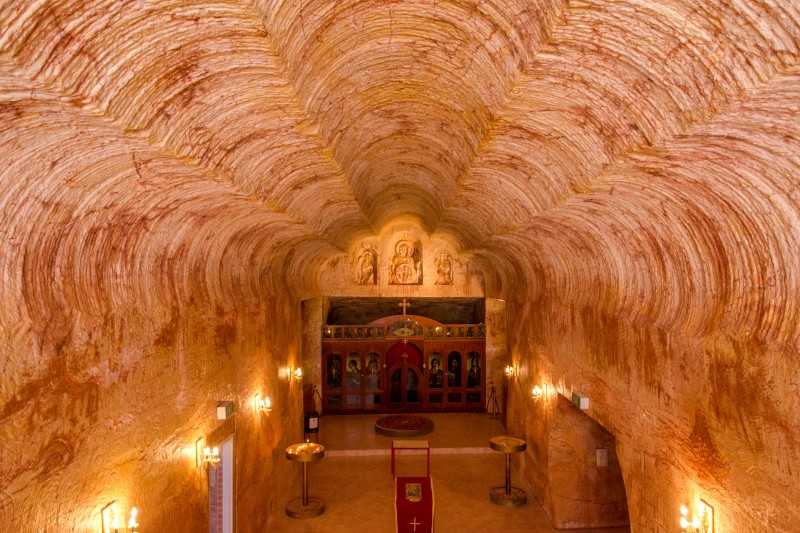

Inside the Underground Church of St. Elijah

Front View of the Interior of St. Elijah

Front View of the Interior of St. ElijahThe Church of St. Elijah in Coober Pedy follows this design, but it is unlike any other Eastern Orthodox church in the world. For decades, the majority of Coober Pedy’s population has lived underground, in dug-out caves that protect inhabitants from the sweltering heat. When construction began on the Church of St. Elijah, there was no question that the complex would be dug underground as well. The excavation was done entirely by community volunteers, including opal miners, artists, and religious experts.

Back View of the Interior of St. Elijah

Back View of the Interior of St. ElijahAt its deepest point, the church is 17 metres underground. It measures in at 7 metres high by 30 metres long. In place of the typical Eastern Orthodox domed roofs are round sandstone arches that mimic the look of the world famous “onion” shaped turrets that are usually perched atop this type of ecclesiastical architectural style. At the front of the church is an incredible iconostasis decorated with artistic renderings of St. Elijah. On either side, the iconostasis is flanked by bas relief sculptures, which were directly carved into the stone. Above the altar room is an intricate, eastern facing stained glass window, the only one of its kind. On Sunday morning, during mass, the entire church is bathed in a rainbow of sunlight.

St. Elijah's Stained Glass Window

St. Elijah's Stained Glass WindowIt was hoped that the excavation of the church, as well as its accompanying community room, parish house, and religious school, would be funded by successes from opal mining. Unfortunately, no opal was found, but, 27 years after its consecration, the Church of St. Elijah remains an icon of Coober Pedy’s rich history. Tourists come from all over the world to see the church, which has been exceptionally maintained because of their generous donations. Parishioners, most of whom are now the third generation of Serbian miners, meet on Sunday mornings for worship. The church has even hosted various weddings. It is now under the control of the first local born Metropolitanate of Australia and New Zealand, Bishop Siluan.

Bishop Siluan

Bishop SiluanThe Church of St. Elijah is not just a church, or a tourist destination, or an incredible feat of architectural engineering. It is, first and foremost, a steadfast symbol of Australia’s diversity and acceptance of integrating different cultures and traditions into mainstream society. Although the road towards tolerance and acceptance has not always been smooth, it has led to the emergence of a country that now has an incredible wealth of world history readily available to its inhabitants.

Next time that you’re opal mining in Coober Pedy, stop by the Church of St. Elijah and say a quick prayer - you never know who might be listening.

References

Metropolitanate of Australia and New Zealand Serbian Orthodox Church. Biography of Bishop Siluan (Mrakic) Newly Consecrated Bishop of the Metropolitanate of Australia and New Zealand. [online] Available at: soc.org.au/en/directory/bishop. [Accessed 03 Aug. 2020].

Orthodox Wiki, (2015). History of the Serbian Orthodox Church. [online] Available at: orthodoxwiki.org(/Church_of_Serbia). [Accessed 03 Aug. 2020].

Priest Alexander Borodin. Layout of an Orthodox Church. [online] Available at: nativityofchrist.net/Layout-of-an-orthodox-church. [Accessed 11 Sept. 2020].

Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral. The Church Building. [online] Available at: orthodoxprayer.org/Divine_Liturgy/ChurchBuilding.html. [Accessed 03 Aug. 2020].

serbia.com, (2016). The most unique Serbian sanctity on the planet: Underground church in Australia. [online] Available at: serbia.com/unique-serbian-sanctity-planet-underground-church-australia/. [Accessed 11 Sept. 2020].